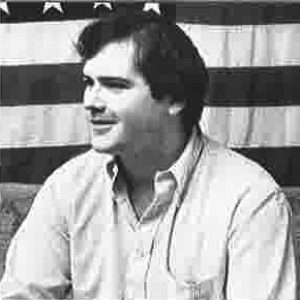

Brian Lyman, who has been immersed in Alabama state politics as a reporter for nearly two decades, was named a 2024 Pulitzer Prize finalist for his “brave, clear, and pointed columns that challenge ever-more-repressive state policies flouting democratic norms and targeting vulnerable populations.”

For Lyman, a 1999 Fordham graduate, it was the latest milestone in a journey that began at the University’s Rose Hill campus a quarter century ago, when he was the opinion editor of The Fordham Ram.

He previously worked at the Montgomery Advertiser, the Press-Register, and the Anniston Star—and last year, he became the founding editor of the Alabama Reflector, a nonprofit outlet that’s part of States Newsroom, a group that aims to bolster state-level reporting across the country.

What was it like finding out you were a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize?

We have this huge story running, and I’ve been deep in editing it, so I was not actually listening to the Pulitzer announcements. A friend who’s working in Nashville texted me, “Congratulations on the Pulitzer!” And I texted her back, “Wait, what?” Then my colleagues ran in telling me, so I may have been the last person to find out.

In your commentary you focus a lot on major issues—crime, the death penalty, transgender youth. How do you pick the topics you want to dive into?

The transgender issue has been going on for almost three years now in Alabama, but the column [cited by the Pulitzer board] was [published in April], when the latest [transgender sports] ban was moving toward passage. It just felt like it was something we needed to let people know. “Oh, by the way, this extremely small, extremely vulnerable group is being targeted by your lawmakers, and we need to pay attention to this.”

Some issues, like the column I did about prisons, legislators aren’t really talking about, because it’s not an issue that wins votes, and it’s something they would rather not deal with. But I’ve been inside those prisons. You don’t need to read the Department of Justice reports on the violence within those prisons to be horrified. So, it was just a way of trying to remind people there’s a huge humanitarian crisis that the state government is not dealing with.

And sometimes it’s both an issue in the news and something that happened in real life. My column about the libraries (“The most dangerous idea in a library? Empathy”) was provoked by my daughter just asking me about the value of reading.

Those issues are at the center of a lot of national conversations too. How do you see your role in covering them in Alabama as they go beyond your state?

I said in the opening column when we launched the Reflector, Alabama is the place where America confronts itself. This is where we see the very best and the very worst of the American character.

Let’s talk about the negative side: We still work under a state constitution passed in 1901 that was framed deliberately to disenfranchise Black Alabamians and poor white [people]. You have a government that’s habitually uninterested in really helping address issues of poverty, which are rampant in Alabama. It’s a government that constantly jumps at moral crises that really don’t have any impact on the day-to-day lives of people.

On the positive side of things, almost every major Civil Rights event that took place between 1955 and 1968 came from Alabama. It’s not just Rosa Parks. It’s not just Martin Luther King. It’s school funding issues, it’s voting issues. New York Times versus Sullivan came out of Montgomery. There are brave men and women in this state who constantly demand better. When they demand more, they lead to these great decisions that have, sometimes slowly, pulled Alabama forward. I feel like our role is just to make sure that all these good people in Alabama know what their state government is doing so they can take the appropriate action to support it or, more often, oppose it.

Thinking back to your time at Fordham, do you have things you learned here that you still use today?

It’s been 25 years since I graduated from Fordham, but I feel like everything I do is basically what I did at The Ram, just more—short ledes, hitting deadlines, making as many phone calls as possible. We learned from our older colleagues, and then we passed it on to our younger colleagues. And we did some great things. One editorial sticks out. An LGBTQ group applied for club status and was denied for whatever reason—this is 1997, I think—and we wrote a very lengthy editorial blasting that decision. I was always very proud that we did that.

Now, on the other hand, it’s obviously a student newspaper, so we had some mistakes. It was fall of 1998, and I think it was Daniel Berrigan who taught a class called Poems by Poets in Torment. It’s the end of the semester, and this ends up on our front page. And this story, I swear goes through six pairs of eyes, including my own, and none of us notice that we have named the class Poems by Pets in Torment. I did not hear the end of that for months.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Kelly Prinz, FCRH ’15.

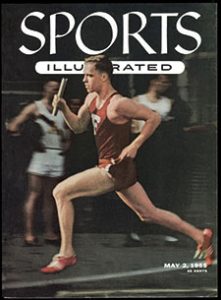

]]>With his wife, Margaret “Posy” Courtney, by his side, two-time Olympic gold medalist Tom Courtney, FCRH ’55, joined the reunion festivities by Zoom from Florida. He took questions from his longtime friend and former Fordham track teammate Bob Mackin, FCRH ’55, who was among those in Loyola Hall.

Prior to the discussion, audience members watched a video of Courtney’s dramatic come-from-behind victory in the 800-meter race on November 26, 1956, at the Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. Courtney—who later said he was proud to be described in the Melbourne newspapers as “The Fordham Ram”—set an Olympic record that day with a time of 1:47.7 before nearly collapsing from exhaustion.

“I was totally, absolutely spent,” he recalled during the reunion event. “All I could think of is, ‘I am in such bad, painful condition, I will never run again.’”

But he ran the next day, and several days later, on December 1, he anchored the U.S. team’s four-man 1,600-meter relay, winning his second gold medal. Because it was the last Olympics not broadcast live on television, he had to call his parents in Livingston, New Jersey, to let them know that he won.

Upon returning to New York, Courtney appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, and on December 12, 1956, Fordham feted him with a dinner at Mamma Leone’s restaurant in Manhattan and a parade in the Bronx—from Poe Park on the Grand Concourse to the Rose Hill Gymnasium, where he received a “huge, triple-decked, silver trophy” from Fordham President Laurence J. McGinley, S.J., The Ram reported the next day.

“Few men have worked as hard and achieved such personal fame in such a short time as Fordham’s Tom Courtney,” Ram reporters Ronald Land and Bill Sturner wrote.

The Fordham University Band led the procession through the Bronx, followed by the student body and the Livingston High School band. Wearing his white Olympics sport coat and a straw hat, Courtney rode down Fordham Road in the back of an open-top orange Cadillac—an experience he recounted in his 2018 memoir, The Inside Track.

“That was a lovely time,” he wrote, “and I was in a convertible with my coach, Artie O’Connor,” a 1928 Fordham graduate who offered Courtney a full scholarship and was the first to suggest that he try to make the U.S. Olympic team. “He was very motivational for me. As we went along, he took my losses much harder than I did. He was a dedicated, wonderful man. He loved Fordham and it helped me to love Fordham.”

After the Olympics, Courtney continued to set world records in 1956 and 1957 before retiring from competition. In 1971, he was one of the first five people, including Vince Lombardi, FCRH ’37, to be inducted into the Fordham Athletics Hall of Fame. He earned an M.B.A. from Harvard University and enjoyed a long career in business, retiring in 2011 as chairman of the board of Oppenheimer Funds.

“Fordham was a wonderful place, and I’m thankful for my experience there—and my scholarship too,” said Courtney, who for many years has been a generous supporter of the University.

Brian Horowitz, FCRH ’10, GSE ’11, head coach of the Fordham men’s track and field and cross country teams, thanked Courtney for his support of the program’s student-athletes.

“Walking into the Lombardi Center each day and seeing the Olympic rings and knowing that you represented Fordham so well is a real inspiration for myself as a coach and for the current members of the team,” Horowitz said. “We hope to continue to make you proud.”

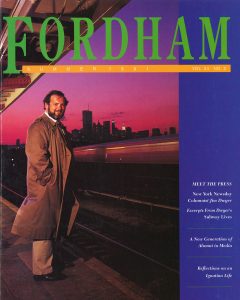

]]>“The angels have a bard. Fordham, and New York City, mourn the death of Jim Dwyer, who was truly the voice of average New Yorkers,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “One could write a book of several volumes extolling Jim’s virtues and his contributions to the city he loved and chronicled. He was a true son of Fordham, and of New York. Our hearts go out to Jim’s wife, Cathy, their daughters, Maura and Catherine, and their loved ones. I know the Fordham family joins me in prayer for them as they grieve Jim’s loss.”

Over more than four decades in journalism, Dwyer sought to tell the stories of everyday New Yorkers and give voice to those on society’s margins, including working-class immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and people convicted of crimes they did not commit. Through his reporting and writing, he worked to help the public understand the impact of major issues and events, most notably 9/11, as well as the inner workings of government agencies and how their decisions affect people’s lives.

“Dwyer had boundless energy, tremendous muscular intellect, and always great empathy for people,” said Thomas Maier, FCRH ’78, an award-winning journalist and author who worked with Dwyer at The Fordham Ram and New York Newsday. “He had a lot of brain, but he had an even bigger heart.”

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, FCRH ’79, one of Dwyer’s Fordham classmates, said his passing was “a great loss” for journalism and for the people of New York.

“He was … a great New Yorker and a powerful voice for many, many years,” Cuomo said. “Jim Dwyer was about the discovery of the truth, and he was brilliant. He was hard working. He also was a poet. He had … the ability to connect with New Yorkers, to take complicated subjects, find the truth, and then communicate it to New Yorkers in a way they understood.”

Covering the Coronavirus

Last spring, in his final columns for The New York Times, Dwyer wrote about the coronavirus pandemic. In one piece, he illustrated how at the height of the pandemic in March, Elmhurst Hospital in Queens was overwhelmed, while “3,500 beds were free in other New York hospitals, some no more than 20 minutes from Elmhurst, according to state records.” In another piece, he delivered a farewell to an Upper Manhattan bar forced to shut its doors permanently: “Coogan’s was the promise of New York incarnate: multiethnic, friendly, welcoming, smart,” he wrote. “The premise of the business was the opposite of social distancing.”

And in a poetic final column, he wove together a tale of his own family history during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic with a chronicle of the thoughts and experiences of three New York City hospital workers responsible for feeding patients during the coronavirus pandemic. He related their ministrations to those of his great-grandmother Julia Neill Sullivan, who in her early 70s “marched pots of food from her hearth across a stony field on a remote peninsula along the west coast of Ireland” to keep her family alive when they were too sick to feed themselves.

“In times to come,” Dwyer wrote, “when we are all gone, people not yet born will walk in the sunshine of their own days because of what women and men did at this hour to feed the sick, to heal and to comfort.”

The Birth of a Big-City Journalist

Jim Dwyer was born and raised in Manhattan, the second of four sons of Irish immigrant parents. His mother, Mary, was a registered nurse at Bellevue Hospital, and his father, Philip, was a custodian in the New York City public school system.

His upbringing and education instilled in him a sense of justice from when he was young, his brother Patrick Dwyer, FCRH ’75, GSAS ’77, LAW ’80, said.

“I do credit Catholic school education for [his sense of justice],” he said. “He had a real conscience [and] he poked everybody else’s conscience. If you didn’t have a voice, he would figure out a way to make your story important to other people.”

He attended Loyola School, a Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side, where Patrick Dwyer said he got a taste for journalism, helping revive the student newspaper there. He said he recently received a call from the president of the Loyola School, who shared a story about a former president who complained about “what a pain” Jim Dwyer was for his work with the newspaper.

“Once a week, you know, [he would] get something out that was complaining about this injustice or that injustice, and what was a pretty fine prep school,” Patrick Dwyer said with a laugh.

He earned a full academic scholarship to Fordham, and initially intended to become a doctor.

In 1976, however, an encounter on Fordham Road changed the path of his life. Dwyer was driving when he witnessed a man having a seizure on the sidewalk. He and a few others stayed with the man and learned that he was a Vietnam veteran who had been having seizures since returning from the war.

Dwyer wrote about the experience for The Fordham Ram, and the article won a national award from the Society of Professional Journalists, due in part to his captivating lead paragraph: “Charlie Martinez, whoever he was, lay on the cold sidewalk in front of Dick Gidron’s used Cadillac place on Fordham Road. He had picked a fine afternoon to go into convulsions: the sky was sharp and cool, a fall day that made even Fordham Road look good.”

Bitten by the storytelling bug, Dwyer was helped along the path to a career in journalism by Raymond A. “Ray” Schroth, S.J., a communications professor at Fordham who became a lifelong mentor and friend, and even served as the family’s priest, presiding over weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Father Schroth, who died earlier this year, helped connect Dwyer with Maier, who was then an editor with the student newspaper.

“I would say it was probably my personal biggest contribution to journalism, getting Jim Dwyer onto The Fordham Ram,” Maier said with a laugh.

By his senior year, Dwyer was editor-in-chief of The Ram.

“I lead a double life,” he said in a 1979 Fordham marketing brochure for prospective students. “I edit The Ram and I’m majoring in science. The newspaper takes 50 hours a week of my time, so if you ask me how I manage to survive academically, I couldn’t tell you.”

Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, a reporter, host, and editor at WNYC, joined The Ram as a staff writer during Dwyer’s senior year.

“I remember walking into the composing room for the newspaper—back then it was made by hand, and the strips of copy that would become columns in the newspaper were hanging on the wall, because they had to dry before they could be pasted onto the board,” he said. “So you can see people’s writing styles next to each other in these strips of paper. And we were all novices, so our writing styles ranged from inept to largely overwritten. But then you saw Dwyer’s strip of writing. And it was just different. It was crisp. It was polished. It was authoritative. And you knew this guy was going on to something big. This guy already got it.”

As an undergraduate, Dwyer began dating a Fordham College at Rose Hill classmate, Cathy Muir, and they were married at the University Church in 1981, with Father Schroth presiding. The year prior, Dwyer had earned a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where he said he truly knew journalism was his calling.

“I would come back from an assignment, my notebooks full, ready to write, and a little smile would break across my lips,” he told Fordham Magazine in 1991.

Finding His Voice Underground

Dwyer got his professional start in journalism in New Jersey, working at The Hudson Dispatch, Elizabeth Daily Journal, and The Bergen Record before taking a job at New York Newsday, where he made the most of a new assignment—subway columnist. His goal was to tell stories of everyday people and how they were affected by the world’s largest transit system, and before long, the paper was billing him as “New York’s real transit authority.”

He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for “his compelling and compassionate columns about New York City.” He had also been part of a team that won the “spot news reporting” Pulitzer for its coverage of a 1991 Union Square subway derailment that killed five people.

Maier, a colleague of Dwyer’s at New York Newsday, said Dwyer’s reporting helped determine what really caused the derailment.

“It was Jim who had the sources and found out that the motorman had been drunk, and that was the front page of Newsday and that was what led to New York Newsday winning the Pulitzer Prize,” he said.

While at New York Newsday, Dwyer also became known for his work related to wrongful convictions, particularly the 1989 case of the Central Park Five, in which five Black and Latino teenagers were arrested for raping a white woman in the park. The teenagers confessed to committing the crime, but Dwyer pointed out that there was no forensic evidence linking them to the scene, and he questioned the police interrogation techniques that led to the confessions.

In one of his pieces on the case, referring to a police transcript, Dwyer wrote, “No New York jury is going to be convinced that this confession contains the language of a New York kid.” A jury convicted the teens, nonetheless. Four of them served more than six years in juvenile facilities, and one, tried as an adult, served more than 13 years in state prisons. In 2002, a convicted rapist confessed to committing the crime. DNA evidence linked him to the scene, and the teens’ convictions were ultimately vacated.

In the 2012 documentary film The Central Park Five, Dwyer reflected on the circumstances that led to the teens’ wrongful imprisonment. “This was a proxy war being fought,” he said. “And these young men were the proxies for all kinds of other agendas. And the truth and the reality and justice were not part of it.”

Patrick Dwyer said his brother pursued stories the same way he played sports in high school.

“As an athlete in high school, he was a bull,” he said. “And that’s pretty much the way he did his journalism. He would keep asking the questions until he got the truthful answer.”

Chronicling Personal Stories of Heroism and Lessons Learned from 9/11

After New York Newsday closed in 1995, Dwyer was a columnist for the Daily News, before joining The New York Times as a reporter in May 2001.

Four months later, he helped shape the paper’s coverage of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. He wrote a series of stories about objects from Ground Zero, like a squeegee a group of people used to escape from an elevator just before the south tower collapsed. And he worked with fellow reporter Kevin Flynn to chronicle in painstaking detail what happened in the twin towers from the moment the first plane hit the north tower until both towers had fallen. Their work, based on hundreds of interviews with survivors, was published as 102 Minutes: The Unforgettable Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers (Times Books, 2005), one of six books he would author or co-author.

In 102 Minutes, Dwyer and Flynn “stitched together a narrative that’s as compelling and suspenseful as it is excruciatingly sad,” Fordham Magazine wrote in 2005. They also documented failures of communication and missteps made by the city and the towers’ developers that came at a terrible cost on that tragic day.

Dwyer credited his science studies at Fordham with helping him tell stories that combined an understanding of technical concepts with a profound sense of human drama.

“If you’re not interested in the engineering of things … you become a servant of whatever people tell you is going on,” he told Fordham Magazine in 2015. “You’re at the mercy of experts.”

Beth Knobel, Ph.D., associate professor and associate chair for graduate studies in the communication and media studies department at Fordham, said that one of Dwyer’s biggest assets as a journalist was an ability to keep his subjects as the focus of his stories.

“He managed to keep himself almost invisible. While so many journalists sometimes make stories about themselves, Jim always kept his focus on the subject,” she said. “The way he used language and imagery spawned a lot of admiration and more than a little jealousy. I wish I had a dollar for every time I read something he wrote and thought, ‘Wow, how does someone put words together like that, with such precision and power?’”

A Commitment to Journalism That Saves and Salvages Lives

Kevin Doyle, FCRH ’78, met Dwyer when the two were undergraduates at Fordham, and they became lifelong friends, each eventually asking the other to serve as godfather to one of their children. “I was a dabbler in journalism [at Fordham]; he was a master of it even then,” said Doyle, a lawyer who has defended death-row inmates in Alabama and who led New York’s Capital Defender Office from 1995 to 2007, when the death penalty was abolished in the state.

He said that Dwyer used the “About New York” column in The Times as a platform to elevate people and causes that he felt needed attention.

“He understood the power that he had, by dint of his journalistic charge, but it never went to his head,” Doyle said. “It was always a tool rather than a prize for him.”

Doyle pointed to Dwyer’s 2012 story about Rory Staunton, a 12-year-old boy who died of sepsis, as an example of journalism that saved “thousands of lives.” Staunton went to NYU Langone Medical Center a few days after diving for a basketball and cutting his arm on a gym floor. He was feverish and vomiting, and he was discharged without being tested for sepsis. Within three days, he died. His parents, in part through sharing their son’s story with Dwyer, embarked on a campaign that eventually led New York to order hospitals “to quickly identify signs of sepsis and begin treatment.”

Five years after the initial story, Dwyer followed up and found that from 2011, before the regulations were implemented, to 2015, 4,727 fewer people died from sepsis.

“Jim wrote about this and as a result now they do [early testing], and you know, it’s saved many, many lives,” Doyle said. “He both saved lives and he salvaged lives with exoneration work.”

In late 2018, Dwyer returned to Fordham to celebrate the 100th anniversary of The Fordham Ram. The editors of the paper had invited him to serve as the keynote speaker at a centennial dinner held in Bepler Commons on the Rose Hill campus.

“If you’re a news reporter, you need to hope for humility,” Dwyer said that night. “And own your own mistakes.”

Knobel said that Dwyer’s address that night was a “love letter” to journalism.

“As in his reporting and column, Jim made it clear to the alums and young reporters there that journalism is really about telling other people’s stories and is one of the greatest ways to spend one’s life,” she said. “The talk was charming and self-effacing and powerful, just like Jim’s work.”

A Generous Colleague, Friend, and Mentor

Maier said that Dwyer was willing to help fellow journalists, whether by recommending a source for a story or even sending a story their way. He recalled that about two years ago, he got a call from an attorney representing a man named Keith Bush, who had been convicted of the murder of a Long Island teen in 1976, but always said he was innocent.

Maier worked on the story for about a year, publishing a 16,000-word investigative report on the case and putting together a documentary on it—all without telling Dwyer, because he didn’t want his friend and former colleague to write about it first.

“I reported out the whole story, that’s almost an entire year, fearful that Dwyer would scoop me on the story for The New York Times,” he said.

Only after Bush was exonerated, on May 22, 2019, did Maier find out that Dwyer was the one who told the lawyer to call him.

Doyle said that outside of work, Dwyer was also known as a loyal, caring, dedicated friend.

“He was always eager to help—he’d drop whatever he was doing. He was a problem solver, inside his family and to his friends,” Doyle said.

O’Grady said that while Dwyer’s passing is a loss for journalism and Fordham, his work and teaching live on in the young journalists he mentored.

“We’re losing a legendary reporter, who was still in his prime, but who spent countless hours mentoring future generations of journalists,” he said. “He’s still with us in the many Fordham students he spoke to and inspired, and people all across the profession who he helped and encouraged.”

Patrick Dwyer said that his brother and his voice will be missed.

“We were extraordinarily proud of him,” he said. “I spoke to a friend yesterday … and I said, ‘You know what, I actually feel that we got it right. The esteem we held him in was apparently shared by everybody else.’”

He is survived by his wife, Cathy Dwyer, FCRH ’79; his two daughters, Maura Dwyer and Catherine Elizabeth Dwyer; and his three brothers, Patrick Dwyer, Phil Dwyer, FCRH ’80, and John Dwyer.

]]>He also earned the homage any reflective opinion writer should pursue: Fair.

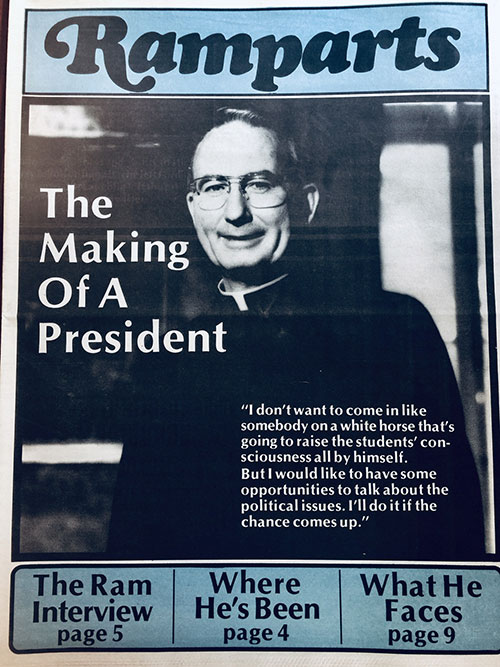

I met Father O’Hare while I was The Ram’s editor in 1984 and he was transitioning into a new career. We were both outsiders. I was billed as the first commuter to become editor. He came to academia from a stint as editor of America, an opinion magazine for which he wrote the column “Of Many Things.”

“I was engaged in telling the world how to behave,” he liked to say.

I wasn’t big on opinion back then, and through much of my journalism career I stood firmly on the facts side of the newsroom wall. These days I facilitate public opinion and write editorials and a column named “Look at it this Way,” a nod to the importance of alternate perspectives.

A few days after his inauguration that fall, Father O’Hare sat for a lengthy interview we published in a special section of The Ram. Executive Editor Dan Vincelette and I weren’t sure what to expect, but Father O’Hare played host like we were members of a secret journalism club. He even shared gossip about legendary advice columnist Ann Landers pursuing him as a possible consultant to help her answer letters.

He put us so at ease that we showed a little hubris in opening the Q-and-A by asking, “Why does Joe O’Hare deserve an inauguration when no other president in the last 50 years has had one?”

While researching his background, we learned he was tagged at America with the nickname “Joe Cool.” We learned why during the interview. No query caused him to flinch, even when we challenged him about divesting holdings from South Africa or about the university declining to recognize the student group Fordham Lesbians and Gays. (He pledged to combat discrimination, but hedged at official approval. Today, Fordham hosts two student groups, the Pride Alliance and the Rainbow Alliance, as well as the Rainbow Rams alumni chapter).

He invited us to gaze into his crystal ball, citing a need to invest in the Rose Hill library (“We really have to do something about it”). It was a promise fulfilled with the debut of the William D. Walsh Family Library 13 years later, a fitting legacy for this man of words.

The conversation continued after the notebooks closed, but Father O’Hare took over asking the questions. An outdoor modern art installation on campus faced hostility from students, and he invited our opinion. He expressed appreciation for our insights. I appreciated being heard.

Lessons that day—and in ones to follow—linger as a master class in the art of rhetoric, of candor, of transparency.

Father O’Hare told us he hoped to be at the helm for at least seven years. He stayed for 19, the longest tenure in the university’s 179 years.

“The trick is to make Fordham [be] perceived as a national institution but keep the character that is distinctly New York,” he said in framing his vision.

He pulled off the trick. That’s not just an opinion.

—John Breunig, FCRH ’85, is the editorial page editor and a columnist for The Stamford Advocate and Greenwich Time.

]]>Partridge-Hicks, a junior at Fordham College Lincoln Center who was then the news editor of The Observer, raced down to the office to write the story. When she got there, the first thing on her computer screen was a video she had worked on earlier in the week featuring students’ reactions to COVID-19.

“[There] was that video of students saying, ‘it’s not that big of a deal,’ and there I was writing that they canceled [on-campus] school,” she said.

“It was just so surreal,” added Partridge-Hicks.

Expanding Coverage

While the COVID-19 pandemic has forced Fordham student journalists to move their operations entirely online and remotely cover the news that’s impacting their community, it’s also given them an opportunity to expand their coverage and try new things.

“What it has done is make us get a little more creative in how we’re seeking out stories,” Owen Roche, outgoing editor-in-chief of The Observer and Fordham College at Lincoln Center junior, studying English and new media and digital design, said. “For example, our arts and culture team is covering a group of Fordham kids who have made a Minecraft server, where they’ve recreated the Rose Hill campus. These sort of things may have flown under our radar or have maybe gotten buried…so this situation is sort of giving us new ways to report…and new things to report on.”

The publication has also been working on “news you can use” stories, such as one on ways to maintain a healthy immune system.

The pandemic has allowed The Observer to fully move from a biweekly to a weekly production schedule. The staff had begun the transition last semester, publishing a print issue biweekly, and articles online in the “in between weeks.”

“The only silver lining I can really identify from this is … we’re producing a full issue every single week now, which we’ve never been able to do,” said Partridge-Hicks, who has since been elected editor-in-chief of The Observer. “It was a goal that we felt maybe was a year off or six months away and we just were able to respond to the situation. I think this has also shown us how much we can achieve digitally.”

For the editors at The Fordham Ram, Rose Hill’s student newspaper, the pandemic shifted their coverage to trying to keep the community informed and provide some sense of normalcy.

“We’ve been trying to highlight student groups and clubs that have been active on social media and online events that they’re putting on,” said Sarah Huffman, a Rose Hill junior and news editor. “We’ve also been doing a lot of coverage of budgets and what is happening with the reimbursements and seniors and commencement. A lot of people have questions right now so we’re just trying to figure out what people care about the most and trying to get answers.”

What’s most important during this time, according to Helen Stevenson, editor-in-chief of The Fordham Ram, is still capturing the student experience. That includes reaching out to student groups, faculty, and staff to see how the pandemic is affecting them.

They’ve also tried to utilize their culture section to include playlists from editors and a “quarantine diary series”—personal features that can help readers stay connected to the Fordham community remotely.

In one recent diary column, Erica Scalise, projects editor emerita for The Fordham Ram, wrote about how she’s struggling to find joy during this time.

“I keep feeling invaded by those classist social media posts about the people who stayed home and read books and cooked meals, about how joy isn’t canceled and laughter isn’t canceled and how I’m somehow supposed to feel compelled to start baking bread because of this,” she wrote. “Yes, I could bake bread while cogitating on all of the ways I could possibly write about New York. I could remain painstakingly hopeful or possibly even amass enough sentimentality to absolve this state of listlessness that lives with me most, if not all, of the time. But I don’t want to make a sourdough starter. I don’t want to take up running or even pretend to like it at all and I’m tired of peeling back layers of myself that were formed in a city where I’m suddenly not.”

Telling COVID-19 Stories

One of the biggest challenges the student journalists have faced is trying to tell COVID-19-related stories in a different way, a problem that many media companies in general are facing, according to Molly Bedford, a design editor at The New York Times who also serves as a visual adviser to The Observer, and an adjunct instructor at Fordham.

“It’s also a time where you need to reinvent your coverage a little bit—it’s a story that needs a new angle, they’re really trying to reinvent new ways to tell similar stories and that’s a challenge across newsrooms everywhere right now,” Bedford said.

Partridge-Hicks said they’ve been trying to cover stories that are unique to their audience.

“We can’t really compete with CNN and The New York Times, but what is beneficial to being college reporters? What’s the information, what’s the data that we can get that makes us stand apart?” she said.

One of the stories that stood out examined the impact on study abroad programs.

“I spoke to nine or 10 students with really different experiences,” she said. “One girl was studying abroad in London, but her parents lived in Tokyo, but they wanted to send her back to the [United] States, and at the time they thought that McMahon and campus housing would be open.”

At The Ram, Huffman said that a piece they published shortly after news broke that campus would be closing for the semester really left an impact.

“[We] wrote a feature about how campus changed as soon as people left and how it was affecting business owners in the community—all the different ramifications of this virus and of the campus shutting down,” Huffman said. “That was emotional to read and work on because everything was changing and we didn’t really know what was going to happen.”

Bedford said she was impressed with the variety of coverage the students were able to tackle.

“They’re able to take this global story and make it relevant to our community,” she said. “Many years from now…students will look back at the time and look to The Observer’s coverage and know what it was like to be a student in 2020.”

A Great Balancing Act

Another challenge for the staff members is the reality of being a student journalist in 2020—having to cover what’s happening and deal with the fact that it’s also happening to them.

“The one thing I learned from the first day on the job is being a student journalist is one giant conflict of interest,” Roche said.

While the staff members have tried to mitigate some of that, by having commuter students report on residential life activities or having students report on programs they aren’t enrolled in, sometimes the emotions are unavoidable.

“When we first got the news that we wouldn’t be returning to campus for the remainder of the semester, it really broke my heart because I’m a current senior,” said Courtney Brogle, outgoing managing editor of The Observer. “They announced that graduation was postponed and that also was so heartbreaking to hear—obviously it was the only option that we had, but it’s still so heartbreaking because you work so hard and build such community and we don’t know when we’re going to see each other again.”

Stevenson said that she usually goes into a “robotic mode,” when breaking news happens, so when she heard that campus was closing for the semester, her adrenaline kicked in.

“I remember receiving the emails that we would not be going back to [campus]and again my fight or flight kicks in—I typed out an article real quick, and then it went out, and not to get too personal but I was bawling,” she said. “It really just hit me that the world would be changing.”

Passion and Commitment

While adjusting to their “new normal” was a challenge, many said they’re grateful to have their fellow newsroom colleagues for support during this time.

“Having production every week and still being able to write and still being able to cover Fordham events and ideas and stories—it’s kind of helping [us]keep sane through all of this, myself included,” Stevenson said.”I know I really do well with the routine and The Ram is such a big part of my life and everybody else’s life when they are on campus.”

Roche said that he was expecting a “downturn in production” with everyone moving to remote reporting, but that never happened.

“We were expecting a dip in productivity and we saw the opposite, which was surprising, and a testament to this staff and all they’re capable of and just the ambitions they have,” he said. “I think this new situation has shown the power of not being afraid to try new things and ask and take risks.”

Bedford and fellow adviser Anthony Hazell, FCLC ’07, said that they were proud of the dedication the students have shown.

“I think most people that age would give up on other things like a student club that they are part of, but I would say that the students on The Observer pulled together in a way that is the strongest that I’ve seen,” said Hazell, who works as the communications director at Bay Ridge Prep, a private school in Brooklyn. “It’s just really impressive the content is stronger than it usually is, it’s strong to begin with, but it’s certainly stronger than it usually is.”

Partridge-Hicks said her goal is to continue to build on that content, using what she’s learned during this time period, when things “go back to normal.”

“That means extensive social media, podcasts, multimedia videos… I think we’re all very proud of what The Observer is producing but we just want to make it more dynamic and more accessible for our readers.”

]]>“Everyone understands that it’s a team effort and that a missed deadline affects everyone,” said Adriana Gallina, editor-in-chief of the Observer. She added that this year’s staff was particularly coordinated with freshmen who “came in super motivated and willing work hard,” and are hopeful about pursuing careers in media.

“We all have a passion for storytelling and it’s what we want to do with our careers, so it hasn’t been hard to keep everyone motivated,” she said.

Laura Sanicola, editor-in-chief at The Ram, said that it’s been a banner year for them as well. She expressed particular thanks to the papers’ business department, which is overlooked during awards season but is integral to keeping the newspaper humming in the black.

Most of her staff is not pursuing communications careers, which makes the awards even more gratifying, said Sanicola.

“Our people are really going in a lot of different directions, like science or business degrees, but the student newspaper does so much to help each of us develop,” she said.”

“I’m really proud of the staff from this year and I look forward to seeing what we can do in the future.”

Both editors credited their advisors, Beth Knobel at The Ram, and Elizabeth Stone at The Observer, with helping them secure the awards .

The awards are listed below:

For The Observer:

Society of Professional Journalists

Finalist, Region 1 Mark of Excellence for in-depth reporting to Adriana Gallina

New York Press Association

First Place for Best Web Site

Second Place for Design

Third Place for General Excellence

Second Place for Sports Coverage to Mohdshobair Hussaini

Honorable Mention for Best News Story to Stephan Kozub

College Media Associations National Media Convention

Third place for the Best Overall Newspaper

For The Ram:

2016 Scholastic Newspaper Awards from the American Scholastic Press Association

First Place with Special Merit

Outstanding Editorial

Outstanding Investigative Reporting to Laura Sanicola

Society of Professional Journalists

Region 1 Finalist: All Around Best Non Daily Student Newspaper

]]>

Do you like costumes? Are you passionate about Fordham?

Do you like costumes? Are you passionate about Fordham?

The University’s Department of Athletics is looking for a few good students to be this year’s official costumed mascot, the Fordham Ram.

The job requires skill, enthusiasm and commitment, said Julio Diaz, associate athletic director for promotions. Some compensation is available.

The Fordham Ram is expected to appear at all home football games and as many men’s and women’s home basketball games as can be arranged. Additional appearances are required at playoff games in all sports and some student and fundraising functions.

Theatrical and athletic ability are a plus; the successful candidate will be expected to do things like dance to Michael Jackson songs, pose for photo-ops with children and alumni, carry flags or banners, incite the crowd to cheer and to generally promote enthusiasm and good sportsmanship at events.

“It’s a bit like being a Disney character,” Diaz said. “You don’t take off your persona.”

Work shifts average three or four hours, Diaz said. The costume has a cooling system to help the Ram stay comfortable while bringing the sports crowd to a boil.

For more information about how to apply, contact Francoisline Freeman at [email protected].

]]>