This was the first time the Gabelli School has been named in this ranking, and its inclusion reflects investments Fordham has made to nurture an entrepreneurial spirit, said Dennis Hanno, Ph.D., who leads the school’s entrepreneurship programming.

“We are gaining momentum,” he said. “We’re dedicating more resources both in our curriculum and in places like the Fordham Foundry,” Hanno said. He noted that the Foundry, which helps students and alumni start viable, sustainable companies, recently celebrated its 10th anniversary.

Hanno cited The Ground Floor course as one example of how first-year students are exposed to entrepreneurship. Every student who takes it pitches a new business idea to a panel of judges at the end of the semester.

The Princeton Review entrepreneurship rating follows other impressive rankings for Fordham’s business school. Poets & Quants ranked the school 21st among the best undergraduate business schools in the country for 2024. In September, U.S. News & World Report ranked the Gabelli School 77th in the country. It also singled out specific undergraduate business programs: The school ranked 13th for finance, 17th for international business, 14th for marketing, 21st for accounting, and 21st for entrepreneurship.

Hanno also noted that entrepreneurship at Fordham extends beyond the Gabelli School. The Fordham Foundry, for instance, holds a separate pitch challenge that is open to all students.

“Whether you’re in business school or not, you’re going to have opportunities here from day one to connect with people who have been entrepreneurs and have worked with entrepreneurs of all different kinds,” said Hanno.

He noted that an expansive view of entrepreneurship can be seen in the work of faculty such as Gabelli School professor Michael Pirson, Ph.D., whose research encompasses humanistic management and sustainable models of business.

“We embrace a broader definition of entrepreneurship to include social impact as a major focus of what we do,” said Hanno, who created a Fordham course called Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Rwanda. He took a group of students to the African nation last spring.

“So if you want to change the world, Fordham is the place for you.”

]]>According to Anthony Annett, Ph.D., a climate change and sustainable development adviser at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, that kind of paradox is just one sign that the way we think about the economy is broken.

This spring, he’s teamed up with lauded economist Jeffrey Sachs, Ph.D., University Professor and director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia, to address the problem in a new course.

At the invitation of Gabelli School of Business professor Michael Pirson, Ph.D., Annett and Sachs are teaching Modern Economics for a Sustainable and Inclusive Planet to a select group of Fordham students. The course, which is open to all undergraduate honors students, focuses on perspectives in economics that promote well-being for all on a healthy planet. Annett said the idea is to learn the philosophical, religious, and modern scientific basis of sustainable development.

It’s part of a larger rethinking of core curriculum at Jesuit business schools that is anchored in principles of Catholic social teaching and humanistic values, he said, noting that theories such as Homo Economicus and Rational-Economic Man that have influenced past generations of economists are being retired.

Having worked as a speechwriter for two managing directors of the International Monetary Fund, Annett had a front-row seat to the ways those ideas foundered, most spectacularly during the Great Recession of 2008.

“I changed tracks after the global economic crisis when I realized this was a crisis of ethics as much as a technical crisis of finance and economics. I started to get much more interested in Catholic social teaching and some of the alternative paradigms out there,” he said.

He and Sachs, a co-recipient of the 2015 Blue Planet Prize for environmental leadership who has twice made Time magazine’s list of 100 most influential world leaders, are publishing a textbook based on the class. It was planned in 2020, but the pandemic has made it feel particularly prescient. The notion that markets will self-correct is not accurate, Annett said, and it isn’t even the first time this has happened.

“After the Great Depression, people realized that laissez-faire economics did not necessarily work in the sense of being self-correcting. You can have dislocations that can last a long time and really hurt people, and that means you need the active intervention of government,” he said.

“We put a lot of emphasis on the role of government. What should government do, what are theories of government from various different thinkers? We pretty much reject the idea of libertarianism, which has influenced how economics has been developed over the past century or so, this idea that the government just needs to step aside and let the market work its magic.”

One of the course’s required readings is Annett’s Cathonomics: How the Catholic Tradition Can Create a More Just Economy, which will be published by Georgetown Press this fall. Annett joked that he’s cited teachings from Pope Francis—who addressed the topic in Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future, (Simon & Schuster, 2020)—so often, that he’s practically a guest speaker.

Sachs also said the pope’s encyclicals Laudato Si’ and Fratelli Tutti, which focus on sustainability and global ethics, are on his mind as he transcribes his lectures for the textbook.

“We need a new way to teach economics that addresses the core economic challenge facing society: achieving a prosperous, fair, and sustainable world economy,” said Sachs, who is the former director of Columbia’s Earth Institute.

“I’m learning an enormous amount every week, often by reading old texts that I had never read before or considering historical analogies that are relevant for our time. I’m also learning that we really can—and should—present economic issues in a new way.”

Alexios Avgerinos, a senior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, said the class was exactly what he was looking for when he moved from Berlin to New York to attend college. He’s writing a thesis on how to structure a firm so that’s it’s not just a profit-maximizing vehicle and will be interning after graduation at a consulting firm dedicated to sustainability. With dual majors in economics and philosophy, he was intrigued by an economics course that featured Aristotle in its syllabus.

“I believe that firms hold so much power these days. Economically speaking, they’re larger than governments, so I think they can have the biggest impact to improve well-being for all people in the world.”

“When you open the Principles of Economics textbook, you are presented with all of these concepts such as utility maximization, and there are so many underlying philosophical assumptions there. You would think they don’t really matter, but they actually change the outcome in the real world.”

Annett concurred.

“In microeconomics, the standard assumption has always been that your goal, as a rational economic agent, is to maximize your preferences, which means you need to get as much stuff on the market that you like, based on your own tastes and preferences,” he said.

“We’re saying, “That’s not really in accord with what a good human being is all about. It should be about making economic choices that are good for you as a human being and good for human society as a whole.”

]]>That was the message of Business with Purpose, a panel discussion held Wednesday, Feb. 13, at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

“Everyone says we need to maximize shareholder value, and that apparently means today. But that’s an ephemeral goal. If you actually thought about the longer-term shareholder value, you have to take into account the environment,” said Paul Johnson, senior advisor at financial services consultant Harbor Peak, LLC, and adjunct professor at the Gabelli School of Business.

“These are shadow liabilities that are unrecognized from an accounting perspective, but they are going to come home to roost.”

Johnson was joined by the Gabelli School’s David Gautschi, Ph.D., the Joseph Keating, S.J., Professor of Marketing; Michael Pirson, Ph.D., associate professor of management systems; and Julita Haber, Ph.D., clinical assistant professor of communications and media management.

The discussion, which was moderated by Sertan Kabadayi, Ph.D., professor of marketing and chair of the marketing area at Gabelli School of Business, was sponsored by the graduate student club Fordham Net Impact.

A Critique of Short Term Thinking

Johnson said the term “long-term” needs to be reintroduced into discussions involving business.

Facebook exemplifies how not to do things, he said, as it puts too much emphasis on growth at any cost, without any consideration for users’ concerns about data collection, privacy, and disinformation.

“You no longer have any customer that would take a bullet for the business. The U.S. is looking at whether or not [Facebook] should be regulated, and no user is going to stand up and say ‘Hold on a second, this is really precious to me,’” he said.

Gautschi, who is also dean emeritus of the Gabelli graduate school, noted that the business world got a black eye in 2007 when the financial markets took a nose dive. This was not new though; in 2001, companies such as Enron, Parmalot, and Global Crossing were found to be operating in unethical, and in some cases, criminal ways.

“The fundamental purpose of business is to generate value and to distribute it. One of the problems that we have is we have a lot of things that are of value. Unfortunately, they’re of negative value, Gautschi said, as he detailed nearly a century of shady behavior in the business community.

“They’re called negative externalities, and they have just been ignored. They need to be brought into the calculus of decision makers within business.”

We Need Problem Solvers

Pirson said it doesn’t help that Americans subscribe to the belief that says we need someone like Elon Musk or Steve Jobs to save us.

“We need a lot of problem solvers, and whether they’re leaders or not doesn’t really matter to me,” he said.

“We’re all on this planet, we all need to problem solve wherever we are. It just matters what kind of problems we want to solve.”

Panelists diverged on how to address short-sightedness. Pirson noted that psychological research shows that humans are innately terrible when it comes to predicting the future.

“It’s easier to actually focus on the current problems and solve them, and see what develops. Nobody predicted the internet. Nobody predicted that Trump was going to win,” he said.

“So, I don’t know if we’re going to do ourselves service by saying we’re going to be long-term problem solvers of some sort. Maybe those long-term problems won’t even exist because we won’t exist.”

Gautschi, who spoke at length about the ways that California utility Pacific Gas and Electric failed to adequately plan for challenges such as climate change, pushed back.

“I will not disagree that beings are limited in their abilities to think long term, but damnit we’ve got to start doing this,” he said.

“The trick for business people, in particular, is to figure out how to adapt.”

To Minimize Blind Spots, Embrace Diversity

One way to adapt? Embrace diversity, said Johnson. If you gather together the broadest possible group of people to give you input, you minimize the number of blind spots you’ll have. Then, you need to create psychological safety where anyone can propose even the craziest ideas without fear of retribution, he said.

“You give me a group of diverse people, average capabilities, and I will crush any group of experts on the planet in any topic, as long as we have some sort of domain expertise,” he said.

Whereas Gautschi, Johnson, and Pirson addressed business from an institutional perspective, Haber, who was the first person to teach a class where students can ride bikes, said it’s important to consider the individual as well. Three-quarters of Americans’ health problems can be traced back to stress, she said. We spend 50 percent of our time in front of a screen, and the average person touches their smartphone 2,600 times a day.

“I see it with my students. What a difference over the years. I give them a five-minute break, and nobody talks,” said Haber, who had all the attendees stand up and stretch with her.

“Loneliness is the new smoking. We’re afraid to say it. ‘Oh my god, I’m not a loser, I can’t admit it.’ This is something that happens, but it happens undercover.”

]]>With help from an environmental engineer, the company discovered that their ventilation system wasn’t regulating impurities in the air properly. According to Stanley, formaldehyde, a chemical found in cotton sportswear that was stockpiled in the store’s basement, was one of the culprits.

“The more we learned about the way that cotton is conventionally grown, the more concerned we got,” he said at an April 6 talk organized by the Gabelli School’s Center for Humanistic Management.

“One of our big concerns is how we look at the challenges of the planet and ensure that our company is not contributing to those challenges and instead contributing to the solutions.”

After making the decision to convert its entire sports line to organic cotton in 1996, Patagonia took employees on a trip to a conventional cotton field and to an organic field in the U.S. The goal was to show them why Patagonia needed to become a more sustainable business.

“The first thing they noticed when we opened the doors to the bus at a conventional cotton field was the smell of the chemicals,” said Stanley, who has been working with Patagonia, a company founded by his uncle Yvon Chouinard, since 1973. “There were also no birds and if you dug your hands in the soil, there were no worms or vegetation.”

In the late ‘70s, Stanley said Patagonia was growing at the rate of about 30 to 40 percent. Though it took about two years to earn back the level of margin that it had before using organic cotton, the experience shaped the company’s approach to manufacturing clothing for climbers, surfers, skiers, and other outdoor enthusiasts.

“Nobody ever came back from one of these trips saying, “This isn’t worth it,’” said Stanley. “We improved our relationship with our customers because we told the same story we did to our customers to our employees and we gained their trust.”

Becoming a Responsible Company

Since its founding, Stanley said, Patagonia—which started as a supplier of climbing hardware—understood the importance of protecting the environment. But back then, the company viewed nature as the “places where we went to play, climb, surf, or ski,” he said.

“It took a couple of other developments for us to understand that our commitment to nature had to be much deeper than just giving 1 percent of our sales every year to an environmental organization,” said Stanley. “Nature is not just where we go to play. The health of our natural systems underlines all of our social and industrial systems, even in this tiny little town where we were based.”

In addition to the use of organic cotton, Stanley said Patagonia has addressed concerns about wool sourcing, synthetic microfiber pollution, animal welfare, climate change, and fair trade and wages in its global operations. In 2017, the company was recognized at the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum for producing quality clothing that doesn’t contribute to waste or the depletion of natural resources. This year, Patagonia was ranked No. 1 in the social good sector of Fast Company’s World’s Most Innovative Companies list.

“There is no shortage of environmental and social problems,” said Stanley. “One of the things that I’m aware of when I’m talking to a group of young people is how much the world has changed since I started working in 1973. It’s a combination of population increase and a very wasteful consumer lifestyle that is putting extraordinary pressures on the environment.”

To discourage overconsumption, Patagonia launched Its Worn Wear program, which allows customers to trade and repair used Patagonia clothing. Stanley argued that buying fewer clothes of high value is a better option for consumers in the long run.

“I think some of the fast fashion companies are experiencing a slow death,” he added. “Fast fashion as a value might still be very good with young people, but [fast fashion companies]are losing millennials when they hit their 20s and 30s.”

Stanley cited Patagonia’s interactive website Footprint Chronicles, which shares information about the company’s supply chain, as an important tool in building transparency.

“Consumers are already very concerned about their food and I think consumers will be willingly concerned about their clothing if they don’t have to fight so hard to get the information,” he said.

]]>“We are on a pathway toward extinction,” said Pirson, an associate professor of management at Fordham’s Gabelli School of Business. “We’re getting rid of the resources that we need. We’re exploiting people and the environment, and we’re already witnessing the dangers.”

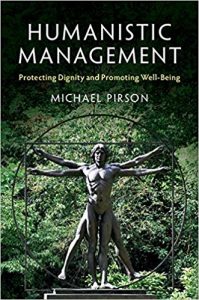

In his new book, Humanistic Management: Protecting Dignity and Promoting Well-Being (Cambridge University Press, 2017), Pirson argues that while chronic issues like climate change and inequality are viewed as large-scale systemic crises, they have been further aggravated by organizations that are only concerned with profit maximization.

“Legitimacy has declined for business and government and on the individual level people often feel unhappy and unsatisfied at work,” he said.

Pirson noted that the dominant economistic paradigm, which many businesses follow today, is oftentimes ineffective because it centers on money, power, and self-interests. Its vulnerabilities can be seen in common occupational woes like sweatshops, child labor, and non-eco-friendly practices, he said.

“This paradigm has been successful to the degree that it has created more shareholder values or larger size organizations, but it has failed in creating wider benefits,” said Pirson.

Pirson believes that the humanistic management model, which focuses on upholding intrinsic values and “dignity,” or respect for people and the environment, can revolutionize the way organizations do business today.

While the humanistic management model acknowledges that money allows employees need to feel safe and acquire things that make their lives better, it also recognizes that we require community, bonding, and purpose to truly achieve success and happiness, he said.

“In a sense, the humanistic notion is a bit broader, but it’s scientifically grounded in terms of the evolutionary traits that have made our species survive,” he adds.

In Humanistic Management, Pirson shows how the paradigm would apply toward research, teaching, business practices, and public policy.

He cites companies like the grocery chain, Whole Foods, and Tesla, which is often fêted for its environmental leadership, as cases where businesses have positively embedded humanistic management into their business protocols.

“None of them are perfectly humanistic,” he said. “But it shows that these practices can be done. They are done not only in specific parts of the world, but across the globe, and you can do them in all kinds of industries. Businesses can be successful or more successful because people trust the organization. Employees like to work for such organizations, because they innovate for the good, and society benefits.”

]]>Through the partnership, students in a new academic course and a complementary practicum—both focused on sustainability and funded by BMW—will work in teams to enhance features of BMW’s new fleet of electric vehicles, the i3 and i8 series. The students will then have the opportunity to share their ideas with BMW representatives.

“Students have a natural understanding about products [like BMW-i]. We don’t need to explain to them what an electric vehicle is and why it’s needed—they all get it,” said Tadhg O’Connor, BMW-i area manager for the Eastern region, during a visit to the Rose Hill campus.

“They’ve grown up consuming these products and they’re used to thinking about how to integrate them into our cities. Their intuition is very valuable to us.”

Carey Weiss, sustainability initiatives coordinator and the instructor for the Social Innovation Practicum, said that the students’ inherent awareness of sustainability is apparent even in these early weeks of the practicum, which is open to both undergraduate and graduate students on all Fordham campuses.

Regarding urban mobility, “Our younger students have brought up the fact that they may never own their own car and have instead talked about ideas like group shares of cars—entirely different models for ownership,” Weiss said.

“These are issues that other generations might not see, but to these 20-year-olds they’re front and center.”

The fact that this generation of college students is immersed in an increasingly urban and sustainably minded society makes partnering with a university ideal, O’Connor said. Fordham is an especially good partner in these efforts, he added—in addition to being designated an AshokaU Changemaker Campus, Fordham has an established a history of operating sustainably, such as prioritizing energy efficiency and powering the Ram Van fleet with bio diesel fuel.

In addition to the practicum, the partnership with BMW underwrites a new academic course, Sustainable Business Foundations, which provides students with a panoptic view of the efforts to make businesses and communities beneficial for “planet, people, and profit” alike.

“The course gives students a perspective on the current challenges related to sustainability, things like urban mobility, infrastructure, food, and public policy,” said course instructor Michael Pirson, PhD, an associate professor of management systems.

“It also helps them gain a keener awareness of the environment—natural as well as social and political—which they’ll need to respond to in whatever career they choose.”

For their midterm projects, students in the class will work in teams to identify a real-life problem for either BMW or the city of New Rochelle, New York, and design a sustainable solution. So far, students have floated ideas about making charging stations for electric vehicles more common and developing smartphone technology that allows drivers to remotely check how much further they can travel before needing a charge.

“We’re trying to change the way we educate not only through academic rigor, but also through applications—providing real-life challenges that we need to figure out and that the students can work on,” Pirson said.

]]>The Jesuit has singled out society’s relentless chase of possessions as a “the great danger in today’s world” and encouraged political leaders to consider financial reforms that stress ethics.

“Money must serve, not rule!” Francis wrote in his Evangelii Gaudiam (Joy of the Gospel), an exhortation published in the year his papacy began.

In some circles, this plea has led to the pope being labeled a socialist and dangerously naïve about financial matters.

But a group of panelists in a Fordham University discussion this week, “None of His Business? Pope Francis on Capitalism,” agreed that the resistance Francis is facing is nothing new, nor is the pope’s belief that people of faith can do better.

Pope Leo XIII took on economic issues in the 19th century in his encyclical, Rerum Novarum, said C. Colt Anderson, Ph.D., dean of the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education.

Leo argued that “some opportune remedy must be found quickly for the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class.”

Leo argued that “some opportune remedy must be found quickly for the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class.”

Francis is doing something similar, Anderson told an audience of more than 50 Fordham faculty, administrators and students at Hughes Hall.

This pope knew that when he said this, that he was [going to face]a lot of opposition,” Anderson said of Francis’ exhortation.

That opposition was often pointed.

“Thank God, so to speak, that his teaching authority is limited to faith and morals, because in matters of economics, he is wide of the mark,” wrote Fox News commentator Andrew Napolitano.

The criticism was part of the pope’s strategy, said Christine Firer Hinze, Ph.D., a professor of theology. Francis has succeeded in getting everyone’s attention.

Anderson said the pope tried to address his critics in his exhortation, and panelists argued that a stand against capitalism without an ethical underpinning is not the same as socialism or even a denunciation of capitalism.

Adam Smith, the 18th-century political economist often cited by capitalists, believed that empathy and capitalism can coexist, said Donna Rapaccioli, Ph.D., dean of the schools of business. That coexistence, she said, is stressed in her school.

“You’ve probably heard the phrase ‘conscious capitalism,’” Rapaccioli said. “Think about companies like Whole Foods, Costco, Patagonia, Chipotle, Southwest Airlines. Even Walgreens has advance inclusion and opportunity. These are successful operations, and they have been able to succeed while respecting people.”

Michael Pirson, Ph.D., an associate professor of management systems for the schools of business and the organizer of the event, agreed. Empathy is the driver of successful human relationships, and businesses that center on the common good have proven to be profitable, he said.

Empathy and business not only can coexist, they must, Francis has said.

“(T)he goal of economics and politics is to serve humanity,” Francis wrote in a 2013 letter to British Prime Minister David Cameron, “beginning with the poorest and most vulnerable wherever they may be, even in their mothers’ wombs.”

Click here to read the story on Gabelli Connect.

Story by John Schoonejongen

Top photo by Joanna Mercuri

Fordham University has been named a “changemaker campus” by Ashoka, a global organization that honors universities for innovative efforts to foster social good and strengthen society.

Fordham University has been named a “changemaker campus” by Ashoka, a global organization that honors universities for innovative efforts to foster social good and strengthen society.

Under the designation “Ashoka U,” Fordham joins 25 other universities and colleges around the nation that are helping change the world through social innovation. They include fellow Jesuit schools Boston College and Marquette University, and other top schools such as Princeton, Duke, Cornell, and Brown universities.

Ashoka is a nonprofit worldwide network that supports entrepreneurial efforts to solve social problems. Marina Kim, co-founder and executive director of the organization’s Ashoka U initiative, said Fordham fits the profile of a changemaker campus for several reasons. The University’s engagement with the community in the Bronx is one. Its focus on research in areas such as health care, technology, environmental protection, social justice, and religious dialogue is another.

The University’s Jesuit identity and commitment to teaching students to be “men and women for others” is likewise a factor, as is service learning, which is “deeply embedded into the campus culture,” Kim said.

“That’s a hugely important foundation on which to build new social entrepreneurship,” she said.

“There are a lot of building blocks already in place, and already strong, that [are]aligned with social innovation as a broader campus-wide strategy.”

Ashoka U’s main focus is strengthening networks of like-minded individuals, both within a university and within the changemaker campus network. Fordham is advancing this effort through its newly formed Fordham Social Innovation Collaboratory (FSIC), said Ron Jacobson, Ph.D., associate vice president in the Office of the Provost.

The three main themes that FSIC will address are global environmental sustainability, human well-being, and social justice and poverty.

“The whole idea of social innovation is something that Fordham as a Jesuit institution has been a part of for almost 175 years, and I think this is just another way of reaffirming the mission of the University,” he said.

“It’s going to break down some of the artificial walls that exist, in terms of curriculum within schools, and in terms of co-curricular activities, where people at one campus know about an event but people at the other campus may not.”

Michael Pirson, Ph.D., associate professor of management systems in the Schools of Business, first proposed the partnership last year. He quickly found others interested in the collaboration, including Jacobson and John Davenport, Ph.D., associate professor of philosophy. Pirson hopes it will help Fordham redefine itself based on its strengths.

“There’s so much complexity, so many big problems and big issues that we’re all faced with,” he said. “In some ways, education is lagging behind in terms of adapting to what folks need to know to make sense of the complex and always-changing environment.”

In addition to integrating curriculums so that they’re more geared toward social innovation, the partnership is leading to various initiatives that create opportunity for students. These include a social innovation workshop course—hosted by the Gabelli School of Business but open to students throughout the University—and a new student organization, the Fordham Intercampus Social Innovation Team.

Jordan Catalana, a Gabelli senior who’s majoring in business administration and minoring in sustainable business, is one of the first students to get involved. She’s a member of the Fordham chapter of the Compass fellowship program, which teaches social entrepreneurship to undergraduates.

Given Fordham’s Jesuit identity, she said, “I’ve been hoping that social innovation at Fordham would be brought to light [and]marketed to more students” as well as to faculty and administrators, she said.

The first Ashoka U-related event took place Sept. 3, when David Bornstein, author of How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas (Oxford University Press, 2007), addressed the incoming class of the Gabelli School.

— Patrick Verel

On Sept. 3, more than 500 Gabelli freshmen gathered on the Rose Hill campus to receive words of wisdom from journalist David Bornstein, whose book How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas (Oxford University Press, 2007) was required summer reading.

The book is a collection of case studies about social innovators such as Jody Williams, whose international campaign against landmines won a Nobel Peace Prize, and Diana Propper, who used investment banking techniques to make American corporations environmentally responsible.

But Bornstein, author of The New York Times’ Fixes blog and founder of the social innovation news site dowser.org, said that he has come to realize that many potential innovators forgo their aspirations because they simply don’t know where to begin.

He recalled asking students at a Midwest college to list every social problem they could think of, and then list every possible solution to those problems. The students were able to fill a blackboard with problems, yet were unable to devise more than a few solutions.

“How could you go through four years of college but only have been exposed to four or five solutions to the 100 problems in your head?” Bornstein said. “What does that do to your energy and your motivation? You have so much awareness about the problems, yet so little awareness about what can be done to solve them.”

Bornstein advised freshmen to spend their time “half on criticality, and half on hope.” If, as brand new students, they committed to pursue solutions as well as problems, then they would be well-poised to effect major social changes by the end of their time at Fordham.

He also emphasized that the ability to make social impact is not limited to people with wealth or status. All it takes is finding the right niche.

“It’s misleading to think that to start social change you have to start your own company,” Bornstein said. “There’s a role for ‘intrapreneurs’ — people who go into hospitals, large companies, or corporations, and change them from within.”

Bornstein said that major social change happens at the intersection of three elements:

- Who you are (What interests you? What bothers you? What kind of work gives you energy rather than drains you of it?)

- Where there is urgent need

- Where opportunities to start solving those needs exist

Once you reach that intersection, he said, take risks and maintain a “pitbull-like tenacity.”

“I encourage you to fail—a lot,” Bornstein said. “Know that failure is the most normal part of this process of social entrepreneurship. It’s a sign that you are doing the right thing.”

Joining Bornstein on a panel following the talk were Frank Werner, Ph.D., associate professor of finance and business economics, Michael Pirson, Ph.D., associate professor of management systems, and Michèle Leaman, changemaker campus director for Ashoka U, an initiative of the international social entrepreneur network, Ashoka.

During the event, Leaman presented a plaque to members of the Gabelli School to officially recognize Fordham University as one of Ashoka’s 25 “changemaker campuses” working to change the world through social innovation.

The conversation about social entrepreneurship and innovation will continue on Sept. 9 at the celebration of the Loschert Endowed Chair in Entrepreneurship. The event will feature Midwest Social Innovation LLC founder Jeff Snell, Ph.D., who led fellow Jesuit school Marquette University to become one of the first ten changemaker campuses.

Contact: Joanna Mercuri

(212) 636-71715

[email protected]

Tesla, an electric-powered car, made its Rose Hill premiere on Oct. 1.

Photo by Patrick Verel

An exotic black car was spotted doing laps around the Rose Hill campus on Oct. 1, but it wasn’t a cause for concern.

The sleek black sedan seen quietly ferrying Fordham juniors and seniors to and from Hughes Hall was a Tesla S60kw, an electric car that travels 300 miles on a single charge.

The visit was part of Sustainable Business Foundations, a class taught by Michael Pirson, Ph.D., assistant professor of management systems at the Gabelli School of Business.

The class, which is the foundation of a sustainable business minor that is open to both Fordham College at Rose Hill and Gabelli students, surveys the principles of sustainable business around three P’s: Planet, People, and Profit.

“We use a theoretical basis for sustainable business and invite companies that represent those to come speak to class. The final assignment for the class is to come up with a sustainable business idea and write a business plan around it,” Pirson said.

Whereas past company representatives have addressed students from the confines of the classroom, the Oct. 1 class was a little more hands-on. As Steve Treacy, a senior at Gabelli who works as a product specialist for the 10-year-old San Carlos, Calif.-based car company, gave students rides around campus, other students peppered Tesla representative Jeff Cuje with questions about the company.

Cuje explained how the S60kw, which has a base price of $70,000, can be charged overnight at any home with a 240-volt connector, at a public charging station, or at one of the company’s “Supercharger” stations opening around the country.

And even though many homes still get their energy via coal-fired plants, Cuje said that, in the long run, it’s still cleaner than cars with traditional internal combustion engines powered by petroleum products.

In addition to Tesla, Pirson has hosted representatives from companies such as Whole Foods, Eileen Fisher, and Green Soul Shoes. Tesla embodies the challenges that sustainable businesses face when tackling issues of transportation and energy, and their advertising model is an example of how many sustainable businesses follow unique paths.

“They’re doing it all word-of-mouth, which is a great strategy because it doesn’t cost as much,” he said.

John McConnell, a senior at Gabelli majoring in finance entrepreneurship, counted himself as a fan.

“The idea of finding a car that runs on a sustainable energy source is not going away, so Tesla is really at the forefront. A lot of other companies have electric models, but that is not their core competency. Tesla’s core competency, as far as what they’re making, is electric cars,” he said.

“It’s really a forward-thinking company.”

After graduation, McConnell hopes to work for a company that is focused on solving the problems of today with the future in mind. General Electric’s “Ecomagination” program, for example, examines companies’ products to see how they might be replaced with something more sustainable.

“Some of them aren’t textbook-sustainable products,” he said. “Fluorescent light bulbs, for instance, aren’t really good for the environment; they just use less energy. But I want to be part of a company that’s looking to solve those issues,” he said.

]]>