Want to find a new way of appreciating the world? Try focusing on how it sounds, says Lawrence Kramer, Ph.D., a Fordham English professor who is also a musicologist and composer.

Kramer has written widely about the importance of sound for appreciating history, art, literature, and current events. Why this approach? Because thinkers dating from Aristotle have treated sight as the most important of the five senses, leading sound to be a little, well, overlooked.

“When you begin to concentrate on sound, all kinds of things come up that traditionally would never have come up,” he said.

In his most recent book, Experiencing Sound: The Sensation of Being, he continues his focus on the humanistic side of sound studies, a field that emerged in recent decades because of advances in sound technology. The overall message is that sound is “the medium by which we measure the sense of being alive,” he said.

The book comprises 66 short essays about “all of the remarkable ways in which sound has affected human lives … and also affected the way in which people feel about being alive,” he said. His hope, he said, is “for people to start listening to the world as hard as they look at it.”

Some encapsulated essays from Experiencing Sound:

The Wind on Mars

In 2018, a NASA Mars lander detected something no earthling had ever heard: the Martian wind. It conveyed that Mars was a world in a way the quiet, windless moon is not. “The sense of a world cannot be established only by what we can see, as we can see the lunar landscape,” Kramer writes. “A planet can be seen, pure and simple. But a world can be seen only if it can be heard.”

The Talking Dead

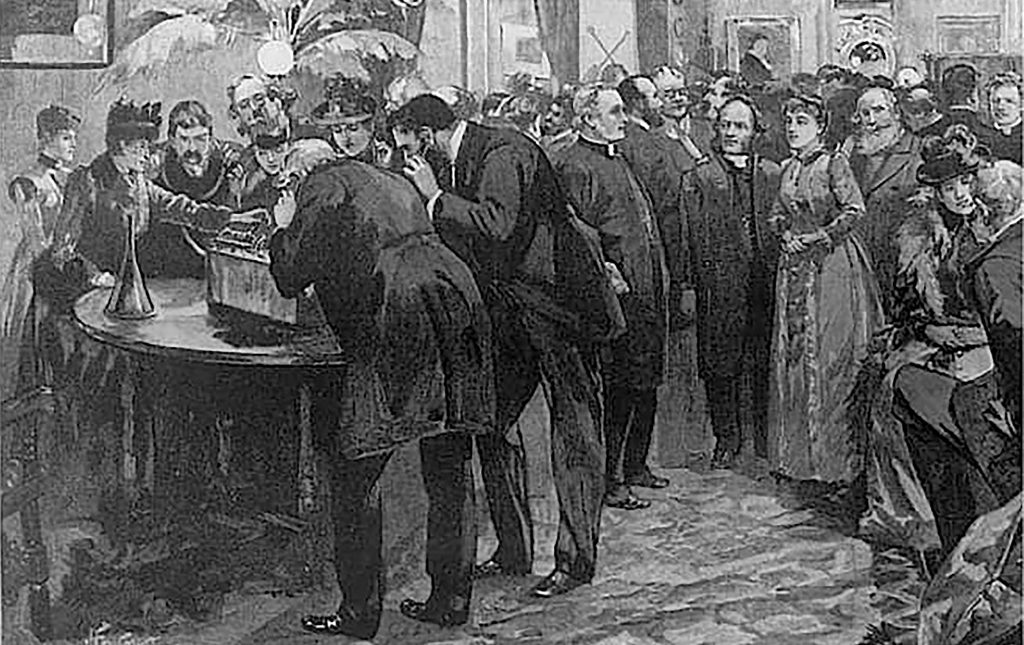

A voice recording conveys life and presence in a way that the visual (i.e., someone’s portrait) does not, as exemplified in 1890, when the voice of the deceased poet Robert Browning was played at an event commemorating him, creating the air of an “extraordinary séance,” one journalist noted. His grieving sister viewed it as a kind of sacrilege, Kramer writes—for her, “it was too alive for comfort.”

Annals of Slavery

In her 1861 memoir Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs describes hiding in an attic’s crawlspace for seven years to avoid being sexually abused by her enslaver. For Jacobs, the street sounds she could hear from the crawlspace were a thread that linked her to life, Kramer writes—until she was able to escape to the North, “what freedom she had was carried on the sound of voices in the street.”

The Contralto Mystique

The author William Styron, in his 1990 memoir Darkness Visible, is dissuaded from attempting suicide when he hears a soaring contralto singer in a movie. It stirred family memories and had a power that was “literally maternal,” Kramer writes, because it reminded Styron of the voice of his late mother singing the same music.

Prisons of Silence

The human need for sound was apparent to Charles Dickens, who wrote “the dull repose and quiet that prevails, is awful” after visiting America’s first penitentiary, Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, where all prisoners were held in solitary confinement in enforced silence. And in a 20th-century Russian gulag, the enforced silence was described as physically stifling by prisoner Eugenia Ginzburg: “I would have given anything to have heard just one sound.”

Minding the Senses

“[K]nowledge comes as much through the ear as through the eye,” Kramer writes. Henry David Thoreau knew this, apparently, with his descriptions of murmuring wind, creaking footsteps in the snow, vibrations in the ear, and the jingling of ice on trees. Even so, today someone returning from a walk will be asked “What did you see?” rather than “What did you hear?” “This,” writes Kramer, “needs to change.”